Repair and Replace

We've got good news, and bad news:We’ve got good news, and bad news: A Morgan Stanley-led banking consortium breathed a sigh of relief Monday, offloading the final $1.23 billion in debt tied to Elon Musk’s 2022-era buyout of social media platform X Holdings (née Twitter).

The first-lien loan priced at 9.5% and a 98 cent on-the-dollar discount, Bloomberg reports, with demand for the issue topping $3 billion. By contrast, the lender syndicate had been fielding bids closer to 60 cents on the dollar only months ago, a discount which would have spelled serious pain.

“If I were Morgan Stanley, I’d be walking on air,” retired Johns Hopkins University finance professor Jeffrey Hooke relates to Bloomberg. “Could you have hoped for a better result as a lender? I don’t think so. [They] were deep in the abyss but got rescued.”

Yet as banks finally clear their balance sheets of the $80 billion in hung deal detritus lodged during 2022’s asset price downshift, primary markets are once again providing little accommodation in the wake of the April 2 tariff “Liberation Day.”

Domestic junk bond issuance stands at $7.9 billion in the month-to-date, Bloomberg relays today, marking the slowest April since 2008, with the $5.1 billion in new leveraged loans representing the fifth-flimsiest single supply month dating to 2013. Banks, which had planned to underwrite $38 billion in euro- and dollar-denominated financing transactions to help fund leveraged buyouts as of the end of March, have since been obliged to house $4.6 billion in orphaned paper.

More broadly, an extended primary market freeze-out would do little to help a notably large contingent of vulnerable credits. The tally of borrowers sporting a Moody’s rating of B3 (“considered speculative and subject to high credit risk”) and below alongside with a negative outlook registered at 16% of the U.S. speculative-grade population as of March 31, little changed year-over-year and modestly higher than the 15% long-term average share. For context, option-adjusted spreads on Bloomberg’s high-yield gauge stood at 347 basis points at the end of Q1, well below the average 480 basis point pickup seen since 1993.

“Lingering speculative-grade distress. . . could worsen if market volatility continues to constrain access to capital for the lower end of [this] population,” analysts at the rating agency wrote last week. “These issuers will find it tough to refinance their upcoming maturities and will have to restructure untenable debt burden[s].”

Recap April 29

Bullish conditions remain in place as stocks shook off some early weakness to post a 0.6% gain on the S&P 500, narrowing year-to-date losses to 5%. Treasurys also remained on the front foot, with 2- and 30-year yields dipping a further two and five basis points respectively to 3.65% and 4.64%, while WTI crude sank to $60 a barrel and gold pulled back to $3,320 per ounce. Bitcoin finished little changed near $95,000 while the VIX continued to deflate at 24 and change.

- Philip Grant

Passive Resistance

BlackRock’s shareholders are being urged to vote against chief executive Larry Fink’s pay at the group’s upcoming annual meeting, setting up a tense remuneration vote at the world’s biggest asset manager for the second year in a row. . .

According to ISS, Fink’s pay is closer to $36.7 million versus the $30.1 million the company disclosed. By “adjusting for the lag in equity grant reporting,” Fink’s awards increased by about 33% from 2023, ISS said. . .

ISS also raised concerns with a new carried interest pay program that BlackRock launched in February. Like Goldman earlier this year, the BlackRock chief’s bonus will include the new award, entitling Fink to a share of the profits generated by the group’s private markets funds for generating growth in this segment.

Stable Coin

Behold the crypto comeback:Behold the crypto comeback: the price of bitcoin has returned to positive territory during the year-to-date, erasing a downdraft that reached 18% earlier this month. The preeminent digital ducat logged a near 12% advance last week, marking its best such performance since the aftermath of President Trump’s re-election last fall.

Meanwhile, blank-check firm Cantor Equity Partners – an affiliate of Cantor Fitzgerald, the brokerage heretofore led by Commerce Secretary Howard Lutnick – detailed plans last week to form a so-called bitcoin treasury company via a merger with Twenty One Capital, Inc., sending investors into a lather as shares vaulted nearly 200% over the four sessions through Friday.

The vehicle, launched in partnership with bold-faced industry names Tether, Bitfinex and SoftBank, provisionally sports a fully-diluted market value of $12 billion by Bloomberg’s lights, triple the $4 billion price tag attached to its cache of 42,000 bitcoins (by contrast, Michael Saylor’s bitcoin acquisition firm Strategy trades at roughly double its net asset value). The frenzied rally speaks to potent institutional and individual demand for such contraptions, notes Keefe, Bruyette & Woods analyst Bill Papanastasiou, with investors “essentially. . . betting on the fastest horse for [accumulating] bitcoin exposure.”

Cantor’s foray marks the third crypto M&A deal valued at $1 billion or higher in the last two months, The Wall Street Journal relays, with Michael Novogratz-led crypto exchange Galaxy Digital preparing a Nasdaq direct listing in the coming weeks following a green light from Trump-appointed regulators at the Securities and Exchange Commission.

Total transaction value across the industry stands at $8.2 billion in the year-to-date per data from Architect Partners, nearly triple the total seen across 2024. “There’s optimism that finally things changed,” Architect founder Eric Risley tells the WSJ. “There’s a genuine interest in the market in taking advantage of this regulatory moment” adds Ryne Miller, co-chair of the crypto practice at law firm Lowenstein Sandler. See the March 28 edition of Grant’s Interest Rate Observer for a closer look at the President’s wholesale, opportunistic embrace of digital assets.

The recent levitation in turn propels an infamous speculative plaything back to the financial fore. The price of Fartcoin reached its best levels since January this morning, as a near 200%, one month rally has pushed its market value to $1.2 billion. That figure outstrips the capitalization of roughly 60% of Russell 2000 Index components.

Recap April 28

A round of consolidation followed last week’s steep rally in stocks, with the S&P 500 shaking off some moderate intraday weakness to log a flat finish, while Treasurys enjoyed a bull-steepening move with 2- and 30-year yields dropping seven and five basis points, respectively, to 3.67% and 4.69%. WTI crude pulled back below $62 a barrel, gold rebounded to $3,348 per ounce, bitcoin remained just south of $95,000 and the VIX settled near 25 after testing 27 at lunchtime.

- Philip Grant

Fizzy Water

A buoyant bounce in skeptic-centric stocks colors this week’s potent rally:A buoyant bounce in skeptic-centric stocks colors this week’s potent rally: the Goldman Sachs Most Shorted Rolling Index powered higher by 4% Thursday to extend its three-day rally to 11%, Accelerate Technologies founder and CEO Julian Klymochko points out, before consolidating that advance today. The basket of battleground names declined by 29% from its Feb. 17 peak through Monday.

Magnificent Seven mainstay Tesla sports a modest short interest of less than 3% of the outstanding float by Bloomberg’s lights, but Elon Musk’s corporate pride and joy represents an apt barometer of broader risk appetite. Shares ripped higher by 10% Friday, capping a 25%, four-day run which cleaved year-to-date losses in half. Musk’s Tuesday comment that he will soon devote far less time to his Department of Government Efficiency side-hustle helped ignite that rally.

The electric vehicle manufacturer could seemingly use some renewed managerial focus. Tuesday also brought word that first quarter adjusted earnings dropped 40% year-over-year to $0.27 per share, trailing the $0.43 analyst consensus which Wall Street had already trimmed by 39% since New Year’s Day.

Real to Real

“There is currently no inflationary risk in Europe,“There is currently no inflationary risk in Europe, and we can now almost say ‘mission accomplished’ when it comes to bringing inflation back to our 2% target” crowed the ECB’s Francois Villeroy de Galhau earlier this week. “The significant deceleration of wages is another proof thereof.”

Average compensation across the euro area rose 3.1% in the year-to-date through early April per the ECB’s latest wage tracker, down from 4.8% across calendar 2024. Nominal CPI, meanwhile, grew at an average 2.3% clip across the first three months of 2025, down slightly from the 2.4% seen last year.

The Old Continent’s inflation-beating pay picture is no outlier. The Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development found last month that annual real wage growth stood in positive territory in 31 of the 34 countries under its analytical purview as of Sept. 30, though the key metric remains below early 2021 levels in 22 of those 34 nations.

Workers in the world’s largest economy are among that fortunate dozen. According to the National Bureau of Economic Research, average hourly earnings have grown at a cumulative 21.4% over the four years through March, outpacing the 19.9% uptick in the CPI over that stretch. By contrast, economist Kathryn Anne Edwards relays in Bloomberg Opinion today that pay gains materially lagged CPI growth during the high-inflation episodes of 1973 to 1983 and 1987 to 1991.

“The takeaway is just how well the economy has moved past the pandemic era’s elevated rates of inflation and how well it was able to ‘zero out’ the net effect it had on wages,” Edwards writes. “As painful as the most recent experience with inflation was, it was relatively tame given how quickly price growth receded and how fast wages recovered and even gained ground.”

The booming – if sporadically interrupted – bull market of recent years has ensured an even sunnier result for the great and good. Thus, median CEO pay among S&P 500 firms at which the boss has held the top spot for at least two years reached $16.8 million in 2024, advisory firm ISS-Corporate finds, up 7.5% from the prior annum. That metric has shown 37% cumulative growth since 2021, nearly doubling the CPI’s 20.6% advance during those four years.

Recap April 25

Stocks rose by 0.7% on the S&P 500 to cap a stellar week for shareholders, as the broad index shook off Monday’s drop to log a near 6%, five-day advance. Treasurys maintained moderate strength with 2- and 30-year yields each declining three basis points to 3.74% and 4.74%, respectively, while WTI crude topped $63 per barrel and gold retreated to $3,308 an ounce. Bitcoin held steady north of $95,000 while the VIX closed before 25 for the first time since “liberation day.”

- Philip Grant

American Idle

We've got boots on the ground:We’ve got boots on the ground: American Airlines pulled its full-year earnings guidance this morning, stating that it will furnish an updated figure “as the economic outlook becomes clearer.” The Fort Worth-based carrier pegged second quarter adjusted earnings per share at $0.75 using the midpoint of management’s range, trailing the $0.96 consensus guesstimate.

“We came off a strong fourth quarter, saw decent business in January and really domestic leisure travel fell off considerably as we went into. . . February,” American CEO Robert Isom relayed on CNBC this morning.

Those would-be vacationers have company in the workaday realm. Keith Waddell, CEO of staffing firm Robert Half, warned yesterday that “business confidence levels moderated” over the first three months of the year as President Trump’s trade-focused agenda took shape, with “client and job seeker caution” serving to “elongate decision cycles and subdue hiring activity.” First quarter revenues at the employment bellwether slipped 8.4% year-over-year to $1.35 billion, short of the $1.41 billion sell-side bogey, while management anticipates a 7% top-line drop during the current period.

A broader consumer barometer likewise points to less than rude health, with Procter & Gamble revealing today that net sales over the three months through March slipped 2% year-over-year to $19.78 billion, short of the sell-side’s $20.11 billion consensus.

P&G now expects organic revenues and core EPS to grow by 2% and 3%, respectively, during its fiscal year ending June 30 instead of the 4% and 6% figures which management reiterated during its late January earnings call. Analysts at Stifel termed those fiscal third quarter results “disappointing,” while peers at JPMorgan characterized the guidance downshift as “worse than feared.”

Thus far, that trio of downbeat updates is par for the course during this unfolding earnings season. Though fewer than 20% of S&P 500 Index components had reported their results by Tuesday, the term “recession” popped up on 44% of those conference calls, the Financial Times reports, citing data from FactSet. That compares to a 3% frequency during calls covering the fourth quarter of last year. “CEOs are a really unhappy bunch at the moment,” Steven Purdy, head of credit research at TCW, observed to the pink paper.

Wall Street’s still-sanguine stance contrasts markedly with that dour mood. Bloomberg equity strategists led by Gina Martin Adams pointed out Tuesday that the bottom-up consensus 2025 earnings growth forecasts for the S&P 500 stands at 7.9%, virtually matching the typical 7.7% profit expansion seen since 2010. “In the face of tariff uncertainty, average growth seems somewhat unrealistic,” Adams et al. wrote, adding that a base 20% levy applied to oversees input costs could spur an outright decline in earnings among the blue chippers.

How to buttress one’s portfolio against that potent potential pressure point? See the brand new edition of Grant’s Interest Rate Observer dated April 25 for a bullish look at one modestly-valued player in an industry described by one investor as “insulated from the peculiarities of these tariffs as almost any that we can think of.”

QT Progress Report

Reserve Bank credit remains little changed at $6.68 trillion, edging lower by $2 billion over the past week. The Fed’s portfolio of interest-bearing assets has declined by $23 billion from the end of March and 25.1% from the 2022 peak.

Recap April 24

Manic price action continues apace, with stocks logging their third straight sharp rally following Monday’s downdraft, leaving the S&P 500 at its best levels since the near 10% relief rip logged on April 9. Treasurys also enjoyed a strong bid with 2- and 30-year yields four and six basis points, respectively, to 3.77% and 4.77%, while WTI crude rose towards $63 a barrel and gold rebounded to $3,345 per ounce. Bitcoin consolidated recent gains at $93,400 while the VIX retreated to 26.5, down a further two points on the day.

- Philip Grant

Stock Symbol

Call it a temporary tattoo, via the New York Daily News:

Earth Day environmental activists defaced Lower Manhattan’s iconic Charging Bull statue Tuesday, then rushed to clean it up before cops arrived, officials said.

Videos on social media and photographs from the scene show a handful of Extinction Rebellion activists spray-painting “Greed = Death” onto the flank of the life-size Arturo Di Modica sculpture on Broadway near Morris St. in the Financial District. . .

Photos show at least one cop removing an activist who was sitting on the bull’s neck as protesters began wiping off the green paint. When more cops arrived, the Bull had been completely cleaned off. No arrests were immediately made, an NYPD spokesman said Tuesday.

Wrap Sheet

If you build it, they will borrow:If you build it, they will borrow: MSCI and Moody’s announced plans Monday to launch a risk assessment service for direct loans, potentially offering new insight into the opaque, $2.5 trillion private credit category.

The firms will each furnish in-house data to help provide monthly snapshots of profitability, leverage and other “forward-looking assessments of the probability of default,” Moody’s managing director David Hamilton told The Wall Street Journal. Such timely data is particularly useful today, “where the uncertainty has been turned up to 11,” he added.

Indeed, recent tariff-induced spasms could serve to further burnish the appeal of closely held credits, as investors have recently turned up their noses at a competing speculative-grade product, pulling a record $6.5 billion from leveraged loans over the week ended April 9 per LSEG Lipper.

Last Wednesday, the U.S. leveraged loan market endured its 14th consecutive session without a new launch, marking the lengthiest primary market freeze since at least 2013 by Bloomberg’s lights and compared to 10 such deal free days across the first three months of this year. Insufficient demand, meanwhile, obliged Wall Street banks to house $4.5 billion in debt backing a pair of acquisitions on their own balance sheets last week, marking some of the first so-called hung deals since the 2022 downturn spurred a raft of scuttled sales.

Accordingly, direct lending is “set to take [market] share again,” a Thursday analysis from Moody’s predicted, as the category represents “a refuge in turbulent times.” With long-frozen IPO markets continuing to exert a chill over leveraged buyouts and exits alike, Moody’s “expect[s] lower-rated companies to lean more heavily on private credit lenders for financing support,” utilizing so-called net asset value lending and similar maneuvers to scare up cash. Waxing interest from institutions such as insurance companies as well as high-net worth individuals will help provide that abutment.

Investors may maintain a shine towards non-traded assets, but those affections have notably overlooked one high profile effort at exchange-traded alchemy. The State Street- and Apollo-managed SPDR SSGA IG Public and Private Credit ETF (ticker: PRIV), which recently launched to substantial fanfare, languishes with less than $55 million in assets, little changed from its initial seeding. Daily trading volumes have likewise shriveled below 4,000 shares on average over the past week from 207,000 shares in daily average turnover during the first five trading days.

“It’s been surprising that demand hasn’t been stronger for PRIV right out of the gate,” VettaFi investment strategist Cinthia Murphy told Bloomberg Thursday. “Appetite for private assets is real, but I think we’ve learned that so are the concerns about the difference in liquidity between the ETF wrapper and the underlying private assets.”

Recap April 22

News snippets suggesting trade-related reconciliation helped stocks stage a steep Tuesday advance, with the S&P 500 climbing 2.6% to narrow year-to-date losses below 10%. Action in Treasurys was more muted, with the long bond dropping three basis points to 4.88% while two-year yields edged to 3.76% from 3.75%. WTI crude climbed towards $64 a barrel, gold retrenched to $3,381 per ounce after touching $3,500 during the wee hours, bitcoin remained red hot at $91,000 and change and the VIX dropped below 31.

- Philip Grant

Beyond Meat

Laws are like sausages, it’s better to let the machines make them. From the Financial Times:

The United Arab Emirates aims to use AI to help write new legislation and review and amend existing laws, in the Gulf state’s most radical attempt to harness a technology into which it has poured billions.

The plan for what state media called “AI-driven regulation” goes further than anything seen elsewhere, AI researchers said, while noting that details were scant. Other governments are trying to use AI to become more efficient, from summarizing bills to improving public service delivery, but not to actively suggest changes to current laws by crunching government and legal data. . .

Rony Medaglia, a professor at Copenhagen Business School, said the UAE appeared to have an “underlying ambition to basically turn AI into some sort of co-legislator,” and described the plan as “very bold.”

Recoup Deville

Retail doubles down:Retail doubles down: The spring selloff has done little to mute animal spirits, with leveraged long exchange-traded funds gathering a net $6.6 billion during the five days through April 11, per a Thursday Bloomberg bulletin. That’s more than double any prior weekly haul over the past two years and roughly ten times the sum flowing to bearish-biased products. Thanks to an influx of fresh cash, shares outstanding across the 50 most popular leveraged ETFs jumped 20% from the April 2 “Liberation Day” through the end of last week, Citigroup-compiled data show.

“Amongst our most active traders, we see a willingness, if not eagerness, to embrace the volatility in hopes of maximizing their profit potential,” Interactive Brokers’ chief strategist Steve Sosnick told Bloomberg, noting that six such leveraged vehicles ranked among the platform’s top 25 most actively traded assets last week. “There’s a generation of investors who have become quite willing to accept risk.”

Indeed, another type of pitfall appears front of mind for that bulled-up cohort: the fear of missing out. “These ETFs are very popular because they help investors get back into the market quickly and aggressively,” observed Matt Maley, chief market strategist at Miller Tabak + Co. “A lot of them are worried that we’ll get another big V-shaped recovery.”

After both the March 2020 Covid swoon and 2022 “transitory” selloff promptly gave way to roaring bull markets, the dip-buying impulse is hard-wired into market psychology. Witness the $4.7 billion in net stock purchases by individuals on April 3 – when the S&P 500 responded to President Trump’s aggressive tariff proposals with a 4.8% drop – the largest single session shopping spree on record by JPMorgan’s lights.

Of course, that strategy works until it doesn’t. BNY Mellon head of markets macro strategy Bob Savage drew the analogy last week of a repeatedly-stretched rubber band which snaps back time and again before, finally, breaking apart. “Outsized moves down [can] have a tipping point linked to volatility and the state of the economy,” Savage wrote. In the meantime, old habits die hard.

QT Progress Report

Better late than never: Reserve Bank credit stands at $6.681 trillion after ticking higher by $3.1 billion over the week ended April 16. The Fed’s portfolio of interest-bearing assets is down $31 billion since the middle of March and remains roughly 25% below its early 2022 peak.

Recap April 21

Stocks were clubbed by 2.4% on the S&P 500 to extend the blue-chip gauge’s two-plus-month drawdown to 16%, though a late rally shaved about a percentage point from the day’s losses. Treasurys fared little better as curve steepening continues apace; the long bond settled at 4.91% after changing hands near 4.5% to start the month. WTI crude retreated below $63 a barrel, gold leapt higher by 3% and change to $3,425 per ounce, bitcoin rose above $87,000 and the VIX settled near 34 after a four point advance.

- Philip Grant

Tourism Board

Is it safe?Is it safe? The recent Treasurys tumult is spurring queasiness in high places, as Bloomberg reports that European Insurance and Occupational Pensions Authority chair Petra Hielkema called the safe-haven status of U.S. government bonds into question last week during a gathering of financial supervisors. Uncle Sam’s obligations have long been described as “risk-free” in some corners, but the Trump administration’s chaotic, antagonistic tariffs regime potentially changes the game.

The truism that markets make opinions may also inform Hielkema’s view, as Bloomberg’s U.S. Treasury Index has returned minus 9% on a nominal basis over the past five years, lagging the negative 6% showing for its global aggregate fixed income gauge.

Conversely, the S&P 500 virtually doubled over the five years through 2024, comfortably outpacing the 74% dollar-denominated return for the MSCI World Index. On that note, foreign investors have veritably covered themselves in red, white and blue in recent years, accounting for 18% of U.S. equity market ownership as of year-end according to Goldman Sachs. That’s the highest share on record, up from about 15% in 2020 and less than 8% throughout the 1960 to 2000 epoch.

Public School

It's raining dollars:It’s raining dollars: Venture capital funding spigots flowed freely at the start of 2025, with U.S. startups gathering $91.5 billion from January through March according to a Tuesday analysis from PitchBook. That represents an 18.5% uptick from the final three months of 2024 and the second-strongest quarterly showing on record. For context, full-year activity during the 2021 everything bubble registered at $358.7 billion, putting the first quarter on pace to challenge that figure.

Of course, current sentiment is far removed from that euphoric post-plague year, with tariff-induced tumult serving to obstruct the public market exit door. “Liquidity that everyone was hoping for doesn’t look like it’s going to happen with everything that has gone on [during] the past two weeks,” PitchBook lead U.S. venture capital analyst Kyle Stanford told TechCrunch. Unicorns (meaning private firms valued at $1 billion and above) Hinge Health, Klarna Group and StubHub have each scrapped IPO plans since President Trump’s April 2 thunderbolt.

Noteworthy concentration, meanwhile, characterized the first quarter burst in VC activity, with OpenAI’s monster $40 billion round itself accounting for 44% of the total sum. Another nine firms gathered $500 million or more, collectively representing a further 27%. “Those deals are really masking the challenges many founders are going through,” Stanford said. “I think there are a lot of companies that are going to need to come to terms with down rounds or getting acquired for large discounts.”

Yet smaller fish have enjoyed a surprisingly hospitable waters in the stock market this year, marking a noteworthy contrast with broader conditions. Thus, 63 firms have raised $100 million or less via U.S. IPOs in the year-to-date through April 9, Bloomberg relayed, racking up a size-weighted average gain of 30%. By contrast, the Renaissance IPO Index, which tracks the largest and most liquid domestic firms listed in the past 24 months, is down 19% since the start of 2025.

“Even in a volatile market, there’s room for well-structured, smaller offerings to gain traction, particularly if they’re positioned around clear narratives [with] focused use of proceeds and a targeted investor base,” Mike Bellin, IPO services leader at PwC, told Bloomberg.

Recap April17

Stocks floated through a forgettable session to settle slightly higher on the S&P 500, wrapping up the holiday-shortened week with a 1.5% loss. Treasurys largely reversed Wednesdays rally with 2- and 30-year yields 3.81% and 4.8%, respectively, up four and six basis points on the day, while WTI crude maintained recent momentum with a push towards $64 a barrel and gold pulled back only slightly at $3,315 per ounce. Bitcoin rose towards $85,000 while the VIX ebbed to just below 30.

- Philip Grant

Luna Module

Crypto trading concern Galaxy DigitalCrypto trading concern Galaxy Digital is set to add some serious heft to the Nasdaq when it completes its IPO as soon as next month, on a pro-forma basis, at least. Thus, revenues registered at $42.6 billion in calendar 2024 per a recent SEC filing, more than double BlackRock’s $20.4 billion last year. Founded in 2018, Galaxy employed 520 individuals as of Dec. 31, compared to 37-year-old BlackRock’s near 20,000 corporate headcount.

But as DL News pointed out Monday, there may be less than meets the eye at Michael Novogratz’s outfit. “Firms in the trading space have different ways of presenting their volumes and the commissions that they earn on those volumes,” Benchmark fintech and digital assets analyst Mark Palmer (who covers Galaxy), told the crypto publication. “In Galaxy’s case, it presents its trading volumes as total revenue.”

The Last Days of Disco

Everything must go!Everything must go! U.S. shoppers showed up in force last month, as March retail sales vaulted 1.4% from the prior month according to the Commerce Department, topping the 1.2% Dow Jones-compiled consensus and marking the strongest sequential showing since January 2023.

“Consumers [are] continuing to spend, and that is ultimately the basis of the U.S. economy,” Bank of America CFO Alastair Borthwick commented Tuesday. “The signals at this point from the consumer are that the economy remains in good shape.”

Yet the April 2 “liberation day” tariffs loom uncomfortably large over that key cohort, potentially driving the recent burst of activity while serving as a headwind against continued strength. There “would appear to be a little bit of front loading of spending, specifically in items that might have prices go up as a function of tariffs,” commented JPMorgan CFO Jeremy Barnum.

To that end, respondents to The Conference Board’s consumer confidence survey for March evinced a less-than cheery disposition towards the commercial backdrop. The Expectations Index – which tracks the short-term outlook for income, business, and labor market conditions – sank 9.6 points from February to 65.2, the lowest in 12 years. Readings south of 80 typically signal recession ahead, The Conference Board relays.

Then, too, the national average credit score tabulated by FICO fell to 715 in February from 717 a month earlier, data released today show, marking only the second sequential decline in over a decade following a near uninterrupted march higher from the fall 2009 lows.

Meanwhile, high-stakes tariff squabbles could serve to keep both enterprises and individuals closer to home. A freshly released poll from the Global Business Travel Association finds that “a significant portion” of the 900 plus industry respondents anticipate warming activity, with only 31% of surveyed travel managers expressing optimism over the industry’s outlook for 2025. That figure stood at 67% in November.

Oversees tourists are increasingly taking a pass on the 50 states, with arrivals to the U.S. by plane declining nearly 10% year-on-year in March per the International Trade Administration. Citing data from IAG Aviation Worldwide, Bloomberg relays that Canadian flight reservations to its southerly neighbor from now through September are off 70% from last year’s pace, while European tourists have throttled back their summer bookings at Accor SA-branded hotels (which include Adagio, Sofitel, Fairmont and Swissotel) by 25% from this time in 2024.

Will spendthrift American leisure enthusiasts manage to pick up the slack? Delta CEO Ed Bastian isn’t counting on it, commenting on CNBC last week that “I think everybody is going into a defensive posture” and that activity “really started to slow” around Valentine’s Day. Late last year, Bastian ventured to predict that 2025 would the “best financial year” in the 100-year-old airline’s history.

Might such malaise extend to other pillars of the consumer economy? See the March 28 edition of Grant’s Interest Rate Observer for a bearish look at one U.S.-listed vacation mainstay which is ramping up capacity into today’s forbidding backdrop, potentially imperiling a premium valuation relative to its industry peers.

Recap April 16

Stocks were clubbed by 2.2% on the S&P 500, though the broad average managed to finish about half a percent above its worst levels of the afternoon, while Treasurys enjoyed broad-based strength with 2- and 30-year yields sinking seven and five basis points, respectively, to 3.77% and 4.74%. WTI crude pushed towards $63 a barrel, gold continued its frenzied rally with a near 4% advance to $3,337 per ounce, bitcoin remained just above $84,000 yet again and the VIX rose just under three points to settle near 33.

- Philip Grant

High and Dry

Mr. Market’s under the microscope:Mr. Market’s under the microscope: Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent maintained a sanguine stance in the face of last week’s outsized government bond selloff, commenting on Bloomberg Television Monday that “we are a long way” from requiring an official response. Even so, Washington has “a big toolkit we can roll out,” he declared, pointing to enhanced buybacks of less-liquid, off-the-run Treasurys as one potential option.

In turn, Deputy Treasury Secretary Michael Faulkender floated the prospect of easing the supplementary leverage ratio Tuesday, a tweak which would permit U.S. banks to add more Treasurys to their own balance sheets (that remedy was indeed employed on a temporary basis during the 2020 tumult).

Such trial balloons are telling, as governments and investors alike struggle to adjust to the Trump administration’s tariffs regime. “The U.S. Treasurys market may have lost – at least temporarily – some of its legendary defensive characteristics,” MFS Investment Management senior managing director Benoit Anne mused to Bloomberg. “In the face of higher risk aversion, Treasurys do not seem to offer currently the protection that they used to.”

A suddenly-parched liquidity picture speaks to those concerns, as the head of Treasury trading at a high-profile U.S. fund told the Financial Times that market depth (as in the quantity of executable bids and offers at a given time) had shrunk by 80% from its typical baseline by the end of last week. “If a steep breeze blew through the Treasury market today, rates would move a quarter point,” quipped Guy LeBas, chief fixed-income strategist at Janney Montgomery Scott.

Those crosswinds duly ripple across the corporate credit complex. Average bid-to-ask spreads have lurched wider across the investment-grade realm in recent weeks, Apollo-compiled data show, with off-the-run bonds – defined as those issued more than two years ago with a deal size of less than $900 million – seeing their gap nearly double to 20 basis points, the widest since the Covid crucible.

That cohort, which accounts for half of the IG market by count, “has become virtually untradable and [is now] effectively a buy-and-hold instrument,” concludes Apollo’s Torsten Slok.

Some investors have instead opted to hit the bricks, pulling a net $6.08 billion from short- and intermediate-duration IG bonds over the seven days through last Wednesday according to LSEG Lipper, the largest weekly outflow since May 2022.

Meanwhile, the recent rebound in equity benchmarks represents a needed reprieve for the suddenly-besieged speculative grade credit realm, with yields on Bloomberg’s junk bond gauge plunging 20 basis points Monday to 8.38%, the best single-day showing since late 2023. That screaming rally comes on the heels of a major cash migration: U.S. high-yield bond funds logged a $9.6 billion outflow during the week through April 9, the largest since early 2023, with leveraged loan funds losing a net $6.3 billion, nearly doubling the previous record figure from December 2018.

Primary markets have likewise remained in deep freeze as spring unfolds, with issuance across high-yield and leveraged loans at just $13 billion in the month through Friday per LSEG, compared to an average $52.5 billion seen over the same period during the past three years. This morning, liquified natural gas concern Venture Global Plaquemines brought $2.5 billion of double-B/double-B-plus-rated senior-secured paper to market, representing the first high-yield sale since President Trump’s April 2 tariff announcement.

Wall Street is undoubtedly watching that deal closely, as the FT reported on Monday that the likes of Citigroup, Morgan Stanley and JPMorgan Chase have each pulled back on planned bond and loan deals in recent sessions on account of weak demand. “Some existing commitments could get stuck on bank balance sheets,” Canyon Partners CIO Jeff Kivitz warned the pink paper, adding that lenders appear “less willing to provide indications for new commitments amidst the volatility.”

Recap April 15

Stocks fluttered lower by 0.2% on the S&P 500 in the first low-key trading session since Trump’s early April thunderbolt, while 10-year yields ticked to 4.35% from 4.38% Monday with the two-year note holding at 3.84%. WTI crude finished little changed at $61.50 a barrel, gold rebounded to $3,228 per ounce, bitcoin edged below $84,000 and the VIX retreated to 30.

- Philip Grant

Capital Expenditure

After all, laws don’t write themselves. From CoinDesk:

Crypto's moment has seemingly arrived in Washington, D.C., and the industry is trying to make the most of it. But as new organizations hatch and leadership shifts at the top advocacy operations, the field of pro-crypto groups trying to carry the torch is more crowded than ever.

No fewer than a dozen groups — including the Digital Chamber, Blockchain Association and Crypto Council for Innovation — are seeking to steer digital assets policies in the U.S., some of them substantially overlapping in their membership bases, funding sources and in the goals they're seeking to accomplish.. .

Congress is chasing several crypto bills, including legislation to set boundaries for crypto markets, oversee stablecoin issuers, curtail digital assets in illicit financing, call for proof of reserves at crypto firms and set up government digital reserves.

Rock of Ages

A “trade war and tariff war will produce no winner,”A “trade war and tariff war will produce no winner,” China’s president-for-life Xi Jinping declared in Vietnam over the weekend. While Xi’s point may survive the exaggeration, gold appears a prominent exception to that dour forecast: spot prices vaulted above $3,200 per ounce for the first time Friday, wrapping up its best week since March 2020 and leaving year-to-date gains at 22% following today’s moderate pullback.

Investors in the Middle Kingdom have certainly taken a shine to the yellow metal, with intense buying interest serving to push local prices to a $20 per ounce premium per Bloomberg. Onshore ETF inflows have likewise set repeated weekly records this year, with the most recent, five-day influx of RMB 12.4 billion ($1.7 billion) nearly doubling the prior such high-water mark. More broadly, physical gold ETFs around the globe logged a net $21.1 billion inflow over the three months through March according to the World Gold Council, the strongest such figure since Russia commenced its Ukraine invasion in early 2022.

Such broad-based interest “helps support and stabilize gold prices even amid external volatility,” State Street Global Advisors gold strategist Aron Chan told Bloomberg. “This demand is less speculative and more strategic or culturally embedded, which means it is stickier and more resilient.”

Wall Street is hopping aboard the bandwagon, with analysts at UBS bumping their 2026 average gold price guesstimate to $3,500 per ounce from $2,900, writing that the bull case “has become more compelling than ever in this environment of escalating tariff uncertainty, weaker growth, higher inflation and lingering geopolitical risks.” Peers at Goldman Sachs call for a $4,000 per ounce bullion price next year, predicting that world governments will accelerate their average monthly purchases to 80 tons from the current 70-ton baseline. “Recent flows have surprised to the upside, likely reflecting renewed investor demand in hedging against recession risk and declines in risk asset prices,” Goldman added.

Though gold’s adversity-hedging bona fides are long established, firms charged with extracting the precious metal have earned a spottier reputation. Thus, the NYSE Arca Gold Miners Index sank by more than 70% on a peak-to-trough basis during the 2008 crucible and more than 50% during the dot.com bubble unwind, materially lagging the S&P 500 during both of those bear markets.

Contrarily, several fundamental factors serve to burnish the present-day bull case, including inviting valuations – both relative to the underlying gold price and projected earnings – alongside improving profit margins and relatively tidy balance sheets. Meanwhile, the seemingly ever-present specter of monetary intervention by Jerome Powell and friends looms as a potent potential tailwind for the group. See the current, April 11 edition of Grant’s Interest Rate Observer for a history-informed look at the risks and opportunities at hand for gold mining investors, alongside a captain of industry’s thoughts on today’s backdrop with a trio of his favorite names.

Recap April 14

Stocks posted a 0.8% gain on the S&P 500, as the broad average settled near the middle of its range following an opening jaunt higher and pullback to unchanged in the middle of the session, while Treasurys managed to bounce with 2- and 30-year yields dropping to 3.84% and 4.8%, respectively, down 12 and 5 basis points on the day. WTI crude consolidated near $62 a barrel, gold ticked lower at $3,211 per ounce, bitcoin finished little changed at $84,800 and the VIX dropped 6.5 points to 31.

- Philip Grant

Play Now, Pay Later

From Billboard:

Tens of thousands of music fans will descend on the California desert this weekend for the first of two iterations of the Coachella Music and Arts festival outside of Palm Springs, Calif.

Approximately 80,000 to 100,000 fans each weekend will have coughed up the $599 ticket price to see headliners Lady Gaga, Travis Scott, Green Day and Post Malone. But ticket [prices are] often just the cost of entry — many of those fans will spend more than $1,000 per weekend on lodging and cough up hundreds of dollars more for food, drinks and merchandise. . .

Approximately 60% of general admission ticket buyers at this year’s festival opted to use Coachella’s payment plan system, which requires as little as $49.99 up front for tickets to the annual concert.

Ranks and File

Join the party: the dollar value of distressed credits (defined as those trading at an option-adjusted spread of 1,000 basis points and above) within the Morningstar U.S. High-Yield Bond Index reached $106 billion as of April 9, LCD relays today, up a cool 40% from one week prior. The distressed ratio likewise lurched to 7.64% from 5.46%, with that 218-basis point rise nearly matching the 221-basis point week uptick logged during the Silicon Valley Bank episode in March 2023.

That regional banking kerfuffle proved an advantageous entry point for junk bond investors, as the ICE BofA US High Yield Index saw its OAS shrink to 265 basis points at the end of last year from more than 500 basis points. Will history rhyme? We’ll know more later.

Safety Pin

Port in a storm, or storm in a port?Port in a storm, or storm in a port? Tariff-induced tumult has hardly spared the Treasury complex, with yields on the benchmark 10-year note – often dubbed the most important price in financial markets – ratcheting higher by about half percentage point over the past five sessions.

By contrast, German 10-year bunds wrapped up the week little changed, clinching the largest gap between those two assets since at least 1989 according to Bloomberg. “Bunds have been one of the only rate markets that has acted as a risk-off asset during recent volatility,” notes Orla Garvey, senior fixed income portfolio manager at Federated Hermes Limited.

While political and financial factors alike figure into the ongoing Treasury rout, Uncle Sam’s deplorable fiscal condition certainly does not help.

Thus, the U.S. budget deficit tipped the scales at $1.307 trillion from October through March, data released yesterday show. That’s up 14.6% year-on-year, after adjusting for calendar-related spending shifts, and marks the largest six-month shortfall on record outside the Covid-era policy panic. Meanwhile, Elon Musk now claims his Department of Government Efficiency will achieve $150 billion in savings during fiscal 2026, rather than a prior $1 trillion bogey (for context, outlays during January through March increased $139 billion from the same period last year).

Gross U.S. public debt to GDP reached 121% as of year-end per the U.S. Office of Management and Budget, up from 92% at the end of 2010. By contrast, Eurostat measures German output-adjusted debt at 62.4% as of Sept. 30 (the most recently available data), down from 81% in 2010. “When volatility rises, you look at those relative debt levels and Germany stands out as being more appealing,” Tim Graf, head of EMEA macro strategy at State Street Global Advisors, tells Bloomberg. “Bunds act as a relative flight to quality in this environment,” adds Fidelity portfolio manager Shamil Gohil.

Instructively, the nascent global safe-haven is undergoing its own metamorphosis. The Financial Times reports that Schwarze Null (i.e., black zero) – a cardboard statue erected in Stuttgart to celebrate Germany’s successful efforts to balance its budget – is now “gathering dust in a government storage room between spare television screens and boxes of Christmas decorations.”

That mothballing move aptly underscores Germany’s pivot from fiscal conservatism, with the Bundestag last month scrapping its so-called debt brake (which caps structural deficits at 0.35% of GDP) and unleashing a €500 billion ($565 billion) spending package. “It is a massive deviation from this German idea of budgetary discipline,” historian Andreas Rödder told the FT.

What’s “cleanest dirty shirt” in German?

Recap April 11

Stocks enjoyed a strong bid, rising 1.8% on the S&P 500 to wrap up a wild week with a tidy 5.7% advance. Treasurys remained mostly weaker as 2- and 10-year yields jumped 12 and 8 basis points, respectively, to 3.96% and 4.48%, though the long bond managed to tick to 4.85% from 4.86% Thursday. WTI crude climbed towards $62 a barrel, gold ripped higher again to $3,235 per ounce, bitcoin advanced to just under $84,000 and the VIX settled just below 36, down 11 points from last Friday.

- Philip Grant

Hoard Meeting

From the Financial Times:

The chair of UBS has criticized proposed reforms to bank capital rules in Switzerland, calling the measures “extreme” and saying they would force the lender to hold 50% more capital.

Colm Kelleher said on Thursday that new rules being proposed by the Swiss government and financial regulators would significantly push up the lender’s capital requirements and could damage its ability to compete internationally. . .

“We strongly oppose these extreme additional capital requirements. UBS is already subject to some of the most stringent capital requirements in the world.”

Perp Talk

Triple-levered ETFs are for pikers.Triple-levered ETFs are for pikers. Stateside cryptocurrency punters are set to add a potent weapon to their speculative arsenal, as Bloomberg reports that regulators may approve perpetual futures contracts in short order. “I think we are definitely moving in a direction of crypto-based derivatives being available in the U.S.,” advises Gabe Rosenberg, partner at law firm Davis, Polk and Wardwell. “To me, it is really just a matter of time.”

The contraptions, which track spot prices and offer exposure to the category without needing to hodl the underlying assets, can be geared up to 100 times the original cash outlay. Perpetual futures often account for up to $70 billion of daily volume on the Binance exchange, relays Kaiko research analyst Adam McCarthy, dwarfing the $20 billion or less in spot market turnover typically seen during a given 24-hour stretch. “Perps have really been the heart and soul of the crypto market over the past decade,” he added.

A broader regulatory reshuffle accompanies that prospective arrival, as the Department of Justice will curtail its efforts to crack down on crypto-related malfeasance per The Washington Post. Deputy Attorney General Todd Blanche detailed the policy pivot in a Monday staff memo, writing that agencies including the Securities and Exchange Commission and Commodity Futures Trading Commission are better equipped to handle such cases. As part of that shift, the DoJ will dissolve the National Cryptocurrency Enforcement Team, a Biden-era initiative designed to “address the challenge posed by the criminal misuse” of the digital ducats.

Those developments are par for the course under the auspices of President Trump, America’s first self-styled crypto commander-in-chief and progenitor of the Strategic Bitcoin Reserve and U.S. Digital Asset Stockpile.

The opposition party takes a dim view of the president’s industry bona fides, which includes a moonlighting gig as “Chief Crypto Advocate” of the Trump family-controlled decentralized finance (DeFi) platform World Liberty Financial.

Last week, Sen. Elizabeth Warren (D-MA) and Rep. Maxine Waters (D-CA) penned a missive asking the SEC to preserve records and communications relating to that side-hustle, writing that “the Trump family’s financial stake in World Liberty Financial represents an unprecedented conflict of interest with the potential to influence the Trump Administration’s oversight—or lack thereof—of the cryptocurrency industry.”

Recent developments suggest that those concerns may fall on deaf ears. Yesterday, the Senate confirmed Paul Atkins as new SEC chair in a 52 to 44 vote, elevating the George W. Bush-era SEC commissioner to the big seat. Atkins has long staked out an antagonistic stance towards the Public Company Accounting Oversight Board and is also a noted crypto enthusiast, with Forbes pointing out late last month that he owns up to $6 million in digital assets.

What surprises might an unfettered crypto market spring upon a financial edifice which seems to be hardly in need of more? See “The two lives of Donald J. Trump” in the March 28 edition of Grant’s Interest Rate Observer for a closer look at that key topic.

QT Progress Report

Reserve Bank credit stands at $6.679 trillion following an $8.5 billion decline over the past seven days. The Fed’s portfolio of interest-bearing assets is down $33 billion from four weeks ago, and 25.1% from its early 2022 peak.

Recap April 10

Yesterday’s reprieve proved short-lived as stocks rolled lower again by 3.5% on the S&P 500, alongside a noteworthy dislocation as the SPDR S&P 500 ETF Trust declined by 4.4%. Long-dated Treasurys also remained under pressure with 30-year yields jumping 14 basis points to 4.86% despite a relatively well-received auction this afternoon, while the two-year ebbed to 3.84% from 3.91% Wednesday. WTI crude fell 3.5% to $60 a barrel, gold jumped 3% to a fresh high of $3,172 per ounce, bitcoin slipped below $80,000 and the VIX settled just above 40 after briefly approaching 55 in late morning.

- Philip Grant

Crank Yankers

White House trade advisor Peter Navarro is “a moron” and “dumber than a sack of bricks,”White House trade advisor Peter Navarro is “a moron” and “dumber than a sack of bricks,” Elon Musk tweeted this morning. The Department of Government Efficiency progenitor and Tesla boss evidently took exception to Navarro’s Monday remarks that the electric vehicle giant “isn’t a car manufacturer [but] a car assembler,” in reference to its use of foreign supply chains. “By any definition whatsoever, Tesla is the most vertically integrated auto manufacturer in America,” Musk rejoined.

Financial and fundamental developments alike may help explain Musk’s caustic mood. TSLA shares now change hands nearly 50% below the post-election peak logged just under five months ago. Citing data from CarGurus and Auto Trader, respectively, the Financial Times likewise reports that used Tesla prices dropped 7% year-over-year in the U.S. and 15% in the United Kingdom last month (that compares to broader EV declines of 1.5% and 10% in those regions).

Worldwide new Tesla deliveries registered at 336,681 across the first quarter, well shy of the 390,000 sell-side expectation and down 13% from the first three months of 2024.

Visiting Day

There can be no assurance:There can be no assurance: The artificial intelligence revolution ushers in a murky future for wage earners around the globe, as the United Nations Trade and Development group reckons that the game-changing technology could impact 40% of all global jobs. “The benefits of AI-driven automation often favor capital over labor, which could widen inequality and reduce the competitive advantage of low-cost labor in developing countries,” the outfit posits.

One North American technology mainstay offers a potential preview of that dynamic. Shopify co-founder CEO Tobias Lütke laid down the law in a March 20 memo, which he posted to social media on Monday:

Before asking for more headcount and resources, teams must demonstrate why they cannot get what they want done using AI. What would this area look like if autonomous AI agents were already part of the team? This question can lead to really fun discussions and projects.

The Canadian e-commerce firm, which operates a fully-remote employment model, shrunk its corporate headcount to 8,100 as of Dec. 31 from 11,600 at the end of 2022.

Meanwhile, the eye-catching appearance of one cottage industry accompanies autonomy’s abrupt ascent. “Fake job seekers are flooding U.S. companies that are hiring for remote positions,” CNBC reports today, with research and advisory firm Gartner predicting that, by 2028, one in four job candidates will be fraudulent.

So-called deepfake software and other AI tools underpin that dubious practice, potentially allowing bad actors to steal company trade secrets and customer data, or install malware to then demand ransom for its removal.

The frequency of such fake job-hunters has “ramped up massively” during the past year, relays Ben Sesser, CEO of tech-focused staffing firm BrightHire. “Humans are generally the weak link in cybersecurity, and the hiring process is an inherently human process with a lot of hand-offs and a lot of different people involved. It’s become a weak point that folks are trying to expose.”

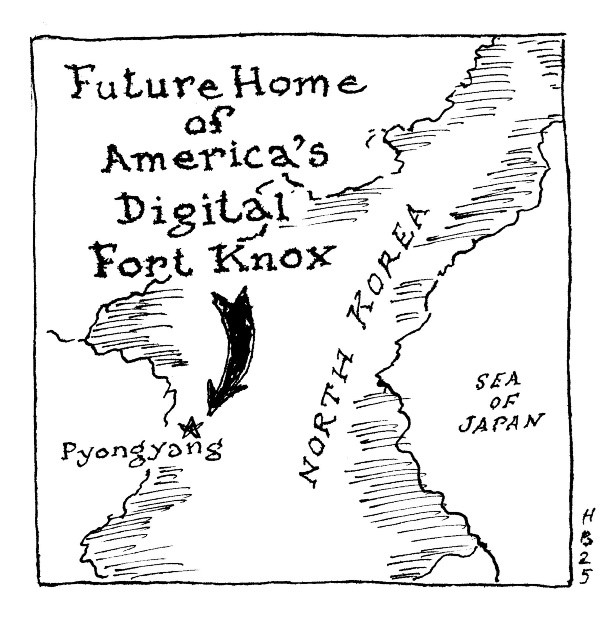

Denizens of Kim Jong-Un’s domain appear to be a particularly prolific cohort. Last spring, the Department of Justice alleged that North Korean imposters “perpetrated a staggering fraud on a multitude of industries,” infiltrating some 300 U.S. companies – including at least a half-dozen Fortune 500 firms – which had unknowingly hired them for remote I.T. roles. The fraudsters ultimately remitted millions of dollars back to North Korea to help fund the Mother Country’s illicit weapons program.

“Every time we list a job posting, we get 100 North Korean spies applying to it,” Lili Infante, founder and CEO of cybersecurity-cum-cryptocurrency startup CAT Labs, advises the financial news network. “When you look at their resumes, they look amazing; they use all the keywords for what we’re looking for.”

President Trump et al., please copy. Source: Grant’s Interest Rate Observer, March 14, 2025.

Recap April 8

Stocks saw another stomach-churning move as the S&P 500 raced higher by 4% after the open, swan-dove to a minus 3% showing in mid-afternoon then staged a (relatively, by current standards) modest rally into the bell to wrap up the day with a 1.6% decline.

That result was outright bullish compared to the action in Treasurys, as 10- and 30-year yields jumped a further 11 and 13 basis points, respectively, to 4.26% and 4.71%, with the iShares 20+ Year Treasury Bond ETF finishing at session lows. WTI crude fell below $59 a barrel, gold rebounded to $2,984 per ounce, bitcoin edged below $77,000 and the VIX rose eight points to 55.

- Philip Grant

Town and Country

Friend request, or friend demand? From Politico:

Mark Zuckerberg is the latest billionaire to shell out tens of millions of dollars for a pricey outpost in Donald Trump’s gilded capital.

For a month, neighbors in Washington’s upscale Woodland Normanstone neighborhood have speculated about the unidentified buyer who paid $23 million in cash for a 15,000-square-foot mansion. The sale was the third-most expensive in city history and was shrouded in secrecy, with real estate agents muzzled by non-disclosure agreements. . .

Real estate pros who have followed the sudden surge in upper-bracket D.C. real estate transactions say a newfound interest in Washington reflects the culture of the second Trump administration — where private-sector CEOs have gotten the message that the way to the administration’s heart is by showing up in person.

“I think it’s [a matter of] proximity and being here,” said Tom Daley, a longtime veteran of Washington’s high-end real-estate game. “It’s the ultimate bow to the man in the White House.”

Rinsed and Repeat

A sea change in stock market ownership accompanied the violent downdraftA sea change in stock market ownership accompanied the violent downdraft seen late last week: hedge funds staged their largest single-day net sales of global equities on Thursday since at least 2010 per Goldman Sach’s prime brokerage desk, with upwards of 75% of that record net selling taking place in North America. Those fiduciaries collectively bumped short positions across U.S. indices and exchange traded funds by 22% over the five days through Friday, the biggest weekly uptick in over a decade.

“I worry that, [following the] April 2 tariff announcement, it will be very difficult to ‘put the toothpaste back in the tube,’ even if or when we see positive developments on the negotiation front,” Goldman’s John Flood wrote, by way of articulating the bear case.

Another constituency proves less inclined to change tack. Retail investors undertook a net $4.7 billion in U.S. stock purchases during Thursday’s downdraft according to JPMorgan, the largest single-session shopping spree in at least 10 years.

Such a dip-buying impulse was notably absent during the Covid-induced meltdown in March 2020, JPMorgan’s Emma Wu relays, but the now-bygone bull market helped bring such tactics to the fore. Thus, retail investors responded to the 4% decline in the S&P 500 over the four weeks through March 27 with a net $32.9 billion of domestic stock purchases according to Vanda Research, equivalent to the 97th percentile of such inflows since 2014.

The steep subsequent selloff shines the spotlight on individuals’ pain threshold, with a Goldman Sachs-constructed basket of retail favorites off by 35% from its mid-February highs. With institutions acting as “heavy sellers” late last week, Goldman’s focus shifts to “the biggest holders of [stocks] – U.S. households – who have not yet shed risk.”

There is plenty of risk to shed, with American households allocating a record 43.5% of assets to the stock market as of year-end per the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, exceeding the 38.4% share seen during the dot.com bubble peak in 2000 (the first quarter figures are set to be released in mid-June). “It’s these crowds who will likely be the arbiter of price action over the next several weeks, as the [corporate] buyback cavalry doesn’t arrive until the end of the month,” Goldman adds.

Recap April 7

Stocks settled lower by 0.2% on the S&P 500 after more early convulsions featuring a mammoth 8.5% peak-to-trough trading range, leaving the broad index lower by about 14% in the year-to-date. Treasurys took their turn in the pain chamber, with 2- and 30-year yields jumping 5 and 17 basis points, respectively, to 3.73% and 4.58%, with the long bond settling at an April high. WTI crude retreated below $61 a barrel, gold remained under pressure at $2,975 per ounce, bitcoin settled at $78,400 and the VIX reached 48, up 26 points over the past five trading days.

- Philip Grant

Like a Bad Houseguest

They're back!They’re back! Negative nominal interest rates have returned to the financial fore following an all-too-brief hiatus, with bid yields on Swiss government debt due in 2027 briefly dipping to minus .0004% this morning. That’s the first sub-zero foray since 2022 for those benchmark two-year notes, which changed hands at 0.36% three weeks ago.

The global tally of negative yielding bonds, which, of course, guarantee a loss if held to maturity, reached $18.4 trillion in late 2020 before melting away during the post-Covid inflation conflagration.

Sleep Some More

Long-dormant capital markets have hit the snooze button:Long-dormant capital markets have hit the snooze button: Buy-now, pay-later outfit Klarna Bank and ticketing middleman StubHub Holdings have abandoned plans to launch investor roadshows next week ahead of New York Stock Exchange listings, The Wall Street Journal reports.

A total of 164 companies staged U.S. public debuts from 2022 to 2024, finds Jay R. Ritter, professor at the University of Florida Warrington College of Business, trailing the 165 IPOs seen during the plague year and just over half the 311 logged during the 2021 speculative bacchanal.

Build a Bear

Add one to the (short) winner’s list.Add one to the (short) winner’s list. Recent market spasms redound to the benefit of would-be homebuyers, with 30-year fixed rate mortgage rates dropping a dozen basis points to 6.63% per Mortgage News Daily. That’s down from nearly 8% on Halloween 2023 and 7.06% at the end of last year.

Ebbing financing costs have already spurred one well-heeled cohort to action. First quarter home sales in Manhattan jumped 29% year-over-year to 2,560, brokerage Douglas Elliman finds, with median prices registering at $1.165 million, up 11% from the first three months of 2024.

Beyond the Big Apple, the drop in rates arrives just in time for spring selling season, CNBC’s Diana Olick points out, with affordability looming increasingly large. Monthly payments for the typical U.S. homebuyer reached a record $2,802 over the four-weeks through March 30, data from Redfin show. Roughly 70% of households cannot afford a $400,000 home at current mortgage rates, the National Association of Home Builders relays, while estimating that the median price of a new dwelling stands near $460,000 (the U.S. Census pegs the latter figure at $414,500).

Tariff-induced price pressures could aggravate that dynamic, as respondents to a Realtor.com survey of homebuilders collectively expect average construction costs to rise $9,200 per unit. “The cost associated with tariffs on building materials gets passed along to new-home buyers, which works against the progress builders have made. . . to grow housing inventory and make homeownership more affordable,” commented Realtor.com senior economist Joel Berner.

Recap April 4

Commentary from Fed chair Jerome Powell expressing little urgency to initiate further rate cuts helped ratchet up the pain in stocks, as the S&P 500 sat lower by another 4.5% as of early afternoon (quitting time for your correspondent: Let’s go Mets!).

Conversely, the Treasury market seems inclined to call Powell’s bluff, with the policy-sensitive two-year yield dropping another 10 basis points to 3.62% after Thursday’s 20 basis point swan-dive.

WTI crude sank below $62 a barrel, gold retrenched to $3,030 per ounce, bitcoin showed impressive resilience at $83,000 and change and the VIX hovered north of 40 after touching 45 this morning.

- Philip Grant

It Happens

Plainspoken RHPlainspoken RH (née Restoration Hardware) CEO Gary Friedman didn’t disappoint during yesterday’s earnings call – which took place during President Trump’s market-roiling tariff announcement – remarking thus after checking the high-end home furnishings outfit’s share price reaction:

Oh, shit. OK. ... I just looked at the screen. I hadn’t looked at it. It got hit when I think the tariffs came out.

And everybody can see in our 10-K where we’re sourcing from, so it’s not a secret, and we’re not trying to disguise it by putting everything in an Asia bucket.

Honesty is the best policy, but Mr. Market is suddenly in no mood to credit managerial forthrightness. RH stock settled lower by 40% and is off 62% in this still-young (believe it or not) 2025.

Separation Anxiety

It's the trade dispute everyone is talking about, Japan versus China.It’s the trade dispute everyone is talking about, Japan versus China. This morning, Beijing’s Ministry of Commerce issued a statement protesting its easterly neighbor’s plans to apply export controls on upwards of a dozen items across the semiconductor supply chain beginning May 28.

“We urge Japan to exercise rational decision making [and] promptly correct its misguided practices,” the MoC said, adding that “China will take necessary measures to resolutely safeguard its legitimate rights and interests.” Back in December, the Middle Kingdom tightened export rules on a quartet of semiconductor raw materials, spurring a Japanese government official to characterize that move to the Financial Times as “some sort of declaration of economic war against the world.”

As protectionism-induced turmoil cascades across the semiconductor industry, news from the White House that the sector will remain exempt from U.S. reciprocal tariffs represents no small silver lining. Major players such as Taiwan Semiconductor enjoy a highly integrated supply chain and assemble most of their products outside the 50 states, Thornburg Investment Management portfolio manager Sean Sun notes to Bloomberg, which could cushion the blow against second-order cost pressures.

Even so, geopolitical strife has already forced one such entrant to adapt on the fly. The Financial Times relays today that Samsung’s chips division has pivoted towards China to the tune of a 54% uptick in exports last year, capitalizing on local stockpiling of artificial intelligence-related equipment in response to U.S. export controls.

By contrast, Samsung’s U.S. business is enduring notable pain, “bleeding” market share to rival Taiwan Semi, which plans to pour more than $100 billion into an Arizona fabrication facility. “Samsung and China need each other,” CW Chung, joint head of APAC equity research at Nomura, told the FT. “Chinese customers have become more important for Samsung, but it won’t be easy to do business together.”

Instructively, business conditions across a trio of prominent Western players left something to be desired prior to the recent escalation of economic hostilities.

Thus, average inventories at Texas Instruments, ON Semiconductor and Infineon Technologies reached 208 days’ worth of stock on hand as of Dec. 31, up a hefty 68% from the average reading over the 10 years through 2023. See the current edition of Grant’s Interest Rate Observer dated March 28 for an informed speculation on the consequences of that buildup, for both economic health at large and the AI revolution in particular.

QT Progress Report

Recap April 3

No relief was forthcoming following the outsized overnight gap lower in stocks, with the S&P 500 finishing at session lows with a near 5% decline, extending year-to-date losses to more than 8%. Treasurys saw frantic bull steepening with two-year yields collapsing by 20 basis points to 3.71% while the long bond ticked to 4.49%, down a routine five basis points on the day. WTI crude tumbled 7% to less than $67 a barrel, gold logged a modest pullback at $3,108 per ounce, bitcoin fell below $82,000 and the VIX rampaged to near 30, up just over eight points.

- Philip Grant

Near and Far

Countervailing winds blow across the investment-grade bond market,Countervailing winds blow across the investment-grade bond market, after a shaky macroeconomic backdrop helped push spreads on Bloomberg’s benchmark wider by 14 basis points over the first three months of this year. That’s the largest such quarterly updraft since the middle of 2022, though option-adjusted spreads remain south of 100 basis points, well below the 168-basis point pickup logged in June 2022.

As Bank of America credit strategist Yuri Seliger points out today, fundamentals within that high-grade cohort remain largely shipshape. March saw a net $80 billion worth of credit ratings upgrades, more than double the average $38 billion seen over the prior 12 months. More constructive ratings actions are likely forthcoming, with the share of IG index bonds on a positive outlook/watch reaching 2.4%, up 10 basis points from February and “well above” the median 1.6% dating to 2010.

Haggle Rock

Someone is going to pay.Someone is going to pay. President Trump has company in his efforts to turn the screws on China, as Bloomberg reports that Walmart “is continuing to push” suppliers to cut their prices by as much as 10% to help offset tariff-related costs.

Notably, those efforts persist three weeks after Communist Party officials read WMT executives the riot act and state media warned that retaliation could be in the cards.

As Walmart prioritizes margin preservation over diplomatic relations, the broader Sino-American grasp for negotiating leverage continues apace. Bloomberg seperately reports today that Beijing “has taken steps to restrict local companies from investing in the U.S.,” with the central planning National Development and Reform Commission withholding approval for such projects in recent weeks.

On that score, Chinese commercial interests may not need further discouragement. Newly announced investment projects across North America registered at just $191 million in the fourth quarter according to Rhodium Group, down more than 90% from the last three months of 2023.

In turn, overseas firms are throttling back within the Middle Kingdom, with net foreign direct investment plummeting $168 billion last year to $4.5 billion, representing the largest single-year decline and smallest such influx since 1990 and 1992, respectively.

The messy aftermath of China’s titanic housing bubble may inform that faltering international project pipeline. The Financial Times reported on Monday that offshore lenders to 62 defaulted property developers have recouped just $917 million since the start of 2021, equivalent to just 0.6% of the $147 billion aggregate face value. For context, recovery rates on defaulted U.S. junk bonds and leveraged loans over the decade through March 2024 stood at 38% and 56%, respectively, according to ICE-compiled data.

Protracted negotiations have yielded little for those hapless creditors, who remain a less-than-urgent priority as China seeks to manage a towering $12 trillion in total developer liabilities per a 2023 guesstimate from the National Bureau of Statistics. “Everyone’s just thrown in the towel,” Debtwire analyst Dominic Soon told the pink paper. “The main problem is really the onshore debt. Without solving that, there’s almost no money that can come out.”

Recap april 2

Stocks staged an impressive intraday rebound for a third straight session, settling higher by 0.7% on the S&P 500 to nearly complete the retracement from Friday’s steep selloff. Tomorrow could be a different story, however, with S&P futures down substantially after Trump unveiled aggressive tariff plans after the close.

Treasury yields ticked modestly higher in bear-flattening fashion, WTI crude rose towards $72 a barrel for the first time since mid-February and gold edged higher at $3,124 per ounce. Bitcoin jumped to nearly $87,000 while the VIX ebbed to 21 and change.

- Philip Grant

Basket Weaver

In one respect at least, leverage is in short supply at CoreWeave. From CNBC:

Wall Street banks waited a long time for a billion-dollar IPO from a U.S. tech company. They’re not making much money from the one they got.

The underwriting discount and commissions paid by artificial intelligence infrastructure provider CoreWeave, which hit the Nasdaq on Friday, amounted to just 2.8% of the total proceeds, according to a Monday filing with the Securities and Exchange Commission. That means that of the $1.5 billion raised in the offering, $42 million went to underwriters.

That’s on the low side historically. Since Facebook’s record-setting IPO in 2012, there have been 25 venture-backed offerings for tech-related U.S. companies that have raised at least $1 billion, with an average underwriting fee of 4%, according to data from FactSet analyzed by CNBC.

Defense Spending

Behold the delicate balance between freedom and security:Behold the delicate balance between freedom and security: Conventionally-safe assets remain de rigueur ahead of tomorrow’s “tariff liberation day,” as evidenced by gold’s latest leg higher above $3,100 per ounce, along with the iShares 20+ Year Treasury Bond ETF’s ascent towards year-to-date highs with a near 5% advance for 2025.

Without substantial clarity from the Trump administration regarding its tariff-related gameplan, “we expect investors to lose increasing amounts of confidence in the global economic outlook,” Morgan Stanley strategists wrote Monday. “We think that both [investors and business leaders will] continue to lose confidence, even after April 2 passes.”

Heightened risk aversion redounds to the benefit of one stock market cohort, with the S&P Insurance Select Industry Index logging an 8% year-to-date advance, comfortably outpacing the broad index’s minus 4% showing (both figures are inclusive of reinvested dividends).

For its part, industry mainstay American International Group marked an evocative milestone Monday, with shares reaching their highest levels since September 2008, shortly before its infamous collapse and de facto takeover by the U.S. government under the weight of a sprawling, misvalued derivatives portfolio.

After failing to turn a profit from its core underwriting business in all but one year from 2008 to 2020, AIG has successfully course-corrected under CEO Peter Zaffino, who took the reins in March 2021. Thus, debt as a share of total capital ebbed to 17% on Dec. 31 from 31.1% in 2022, while the combined ratio – operating expenses plus claims costs divided by net premiums earned – registered below 92% during each of the past three years. That compares to an average of 105.7% over the half decade through 2021.

Not taking those achievements lying down, Zaffino laid out ambitious operating targets at Monday’s investor day including a 13% return on equity by 2027 versus the 9.1% seen last year, while authorizing a $7.5 billion share repurchase (which includes $3.4 billion remaining under a prior plan), equivalent to about 15% of its market cap.

“Over the past five years, AIG has undergone a dramatic shift, evolving from a complex conglomerate into a streamlined property and casualty insurer,” analysts at Deutsche Bank wrote March 6. “Many investors, particularly those who do not closely follow the insurance sector on a day-to-day basis, may not fully appreciate the extent of this restructuring, which has included significant de-risking of its balance sheet and a strengthening of its underwriting practices.”

Featured as a pick-to-click in the Nov. 22 edition of Grant’s Interest Rate Observer, AIG has since generated a 15% return, compared to a 5% loss for the S&P 500. The stock now changes hands at just over 14 times consensus 2025 earnings forecasts, up from about 11.5 times on publication date.

Notably, AIG’s latest profitability-boosting efforts include the wholesale embrace of a foremost Wall Street fad. The firm detailed plans Monday to allocate between 12% and 15% of its general insurance portfolio to private credit, up from the current 8%, to help offset declining investment income following the Federal Reserve’s recent rate cuts. Private equity holdings will likewise rise to between 6% and 8% of portfolio assets from today’s 5% share.

Recap April 1

Stocks notched their second straight hard-earned green finish, advancing by 0.4% on the S&P 500 after toggling across the unchanged line several times during the session. Treasurys rallied in bull-flattening fashion with 2- and 30-year yields dipping two and seven basis points, respectively, to 3.87% and 4.52%. WTI crude held above $71 a barrel, gold consolidated recent gains at $3,119 per ounce, bitcoin ticked above $84,000 and the VIX edged below 22.

- Philip Grant

Arrested Development

The age of "kidults" is upon us.The age of “kidults” is upon us. Citing data from analytics firm Circana, the New York Post reports that grownups represented 28% of global toy sales last year, up 2.5% from 2022 to surpass all other age groups, including preschoolers.

That eyebrow-raising trend has not escaped the attention of relevant purveyors, with Lego marketing 13% of its 563 newly-released sets last year as “specifically designed” for 19-year-olds and up.

“We're seeing a good amount of growth with adult consumers,” Hasbro chief financial officer Gina Goetter relayed at a December conference. “In fact, over the past year, I think 40% of adults bought a toy for themselves.” Ynon Kreiz, CEO of Mattel, told listeners-in on the March 13 earnings call that the toymaker will be “leaning further into momentum with adult fans.”

Goods and Plenty

Revived price pressures could make for an uncomfortable pairing withRevived price pressures could make for an uncomfortable pairing with President Trump’s April 2 “Tariff Liberation Day,” as The Wall Street Journal highlights an unwelcome trend change across physical products. Thus, the core goods component of the Consumer Price Index (exclusive of food and energy) edged lower by a cumulative 1.7% over the eight years through 2019, cushioning an average 2.7% annual uptick in services such as housing, healthcare and education over that stretch.

Following a post-Covid surge and subsequent retrenchment over the 12 months through last September, core goods inflation has since ticked higher by 0.1% per month on average, reaching a 0.2% sequential clip in February and spurring Fed chair Jerome Powell to flag “high readings” from that metric during his March 19 press conference.

“The recent data are telling us that, for goods, you won’t have the same deflationary impulse as you did during the 2010s,” TS Lombard chief U.S. economist Steven Blitz told the Journal. Inflation as measured by the Personal Consumption Expenditures gauge will register near 3% in 2025, Blitz reckons, well north of the Federal Reserve’s 2% bogey.