For the un-meek

If something can't go on forever, it won't. To that famous axiom, we append a corollary. In a financial context, the definition of "forever” depends on the quality of a capital structure. Load up a balance sheet with debt, and forever can be over in a flash.

Now under way is a bullish speculation on a bearish set of circumstances. We focus on a pair of bruised offshore oil-drilling businesses: Atwood Oceanics, Inc. (ATW) and Transocean Ltd. (RIG). Each is listed on the New York Stock Exchange, each is leveraged and each could yet--in an adverse debt and oil-price situation--blow up in the face of a hopeful punter.

In a Feb. 29 blanket downgrade of a half-dozen offshore drillers, Atwood and Transocean among them, Moody's collapsed the bearish argument into two sentences: "Significantly reduced upstream capital spending and the declining creditworthiness of upstream customers coupled with a steady supply of newbuild rigs entering an already over-supplied rig market will keep day rates under heavy pressure. Leverage and cash-flow metrics are expected to deteriorate sharply as current drilling contracts roll off or are replaced by contracts with lower day rates.” Thus, Atwood was demoted to Caa1 from Ba3 (with a negative outlook) and Transocean to B2 from Ba2 (with a stable outlook).

The shrunken oil price is the besetting problem, the absence of demand for drilling services the deflating consequence. The capital goods that shone so brightly with oil at $107 a barrel--the deepwater semi-submersible rigs, jackup rigs, drillships, harsh-environment semi-submersibles, midwater semi-submersibles, high-specification jackups--have come to look a lot like rusted steel with oil at $36 a barrel.

Of course, the eye focuses most on the rust, physical and financial, at the bottom of the cycle. Let us take this opportunity to say that we do not know if this is the bottom of the cycle. We stand by our hopeful working hypothesis of Jan. 29, which is that low prices are doing their painful, constructive, bullish work. In the offshore-drilling industry, old rigs are being mothballed or turned to scrap. New rigs, with which Atwood is especially well-stocked, will be the first to find work, come the cyclical turn.

"The intensity of the current downturn,” P. Cary Lowe, chief operating officer of Ensco Plc., told dialers-in on the fourth-quarter conference call, "while very challenging in the near term, will also be the catalyst to drive out excess supply through the scrapping of older rigs and cancellation of certain new builds, which in the mid-to-long term will be positive for our sector.”

We judge that Atwood and Transocean are reasonable candidates for survival. Atwood boasts a modern fleet; Transocean, the deepest backlog of work in the business. The respective quoted yields on the companies' publicly traded debt are the visible measures of uncertainty. Both companies happen to have floated issues of 6½% notes maturing in 2020. Atwood's are quoted at 50.37 to yield 28.35%, Transocean's at 70 to yield 15.8%.

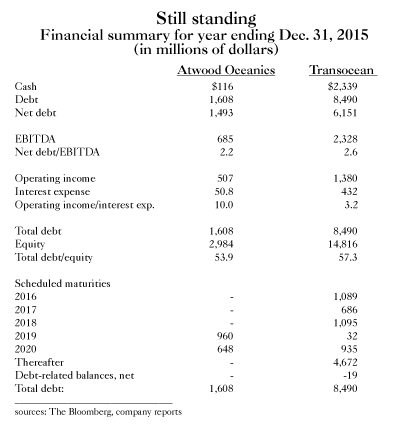

Financial summary for year ending Dec. 31, 2015 (in millions of dollars)

"The biggest risk for Atwood,” Sajjad Alam, an analyst at Moody's, tells colleague Harrison Waddill, "is re-contracting risk. For all their rigs--other than the two new drillships--contracts end this year. So, unless they find work for those rigs, they'll have to depend on cash flows from those two drillships to support debt. They also have some remaining payments they have to make on two additional ships under construction through 2018, so they need to have access to some sort of external funding, and the credit facility that they're relying on has a covenant attached to it which they'll probably blow through in the earlier part of 2017.”

Atwood, which declined to come to the phone when Waddill called, has issued projections of cash flow, cash on hand, capital spending and other vital signs that point to survival through 2018 (though we are unaware of the oil-price assumptions that accompanied this guidance). If the oil-price recovery accelerates, worry will be moot. Otherwise, the No. 1 concern will be the bank line, which topic Atwood's CEO, Robert J. Saltiel, addressed on the Feb. 3 earnings call. "Given the uncertain timing of our industry's recovery,” said Saltiel, "we recognize that there's a risk that the covenants on our revolving credit facility could be stressed at a lower point in the cycle in late fiscal 2017, potentially limiting our access to these funds.” The CEO was referring to the covenant that caps the maximum allowable ratio of net debt to EBITDA at 4.5:1, compared with a Dec. 31 reading of 2.2:1.

Saltiel wanted his auditors to know that the company wasn't just wishing and hoping: "We're in discussions with our lead bankers now . . . and recent discussions are signaling a growing flexibility regarding covenant modifications as this issue becomes more widespread across the industry.” Not a few encumbered oil and gas businesses have achieved such modifications in recent months. The list includes C&J Energy Services, Ltd., Chesapeake Energy Corp., Energy XXI Gulf Coast, Inc., Premier Oil Plc. and EnQuest Plc. Constant readers will recall that NOW, Inc. (Grant's, Jan. 29), a kind of universal hardware store for energy producers, has managed to eliminate its interest-coverage-ratio covenant. Then, too, concerning Atwood's negotiating position, Christine Besset, associate director of commodities, materials and real estate at Standard & Poor's, observes: "They have high-quality assets, and two of their new drillships are unencumbered, so they could potentially add those to collateral in exchange for relaxed covenants.”

On last month's earnings call, the Transocean front office dodged a question about oil prices. There is no one restorative, break-even price, came the non-reply; observe, for instance, the company said, that Statoil ASA is penciling in $30 per barrel or less for the immense Johan Sverdrup oil field in Norway, now in the planning stage. As for the price of oil that would balance incremental supply and demand over the long term, Transocean (like many another observer) reckons that $90 is the minimum.

The risk to Transocean, Ben Tsocanos, an oil- and gas-ratings director at S&P, tells Waddill, "is a combination of low utilization, committed capital spending and significant debt maturities.” Then he offered a caveat, to wit: "I think they are deferring capital spending as much as possible. The dividend has been reduced, but they have very large debt maturities looming. They have a lot of cash [$2,339 million] and an undrawn credit facility [$3,000 million]. So that's why they are a BB-plus and not lower, because they have all that cash. If they can't refinance, they could still pay off the maturities.”

One of these days, some genius will take his oil-drilling company into a cyclical downturn debt-free. He or, for that matter, she will borrow at the bottom of the market to buy up cheap assets. That time is not now, as far as we know. Certainly, Transocean does not currently resemble that shrewdly managed enterprise. At least, though, it is repaying the debt it probably ought not to have incurred. After retiring $1 billion this year, says Philip Adams, an analyst at GimmeCredit, it stands to close 2016 with a cash balance of $1.9 billion. "As it concerns their credit facility,” our informant adds, "the revolver has a typical investment-grade covenant package consisting of one ratio: a consolidated-indebtedness-to-total-tangible-capitalization limit of 60%. Transocean says it is currently below 40%; my raw GAAP ratio is 36%.”

Not the least of the appeals of ATW and RIG is that they have so few friends. Concerning Transocean, the consensus of analysts surveyed by Bloomberg is one lonely buy, 15 holds and 22 sells. For Atwood, the analytical skew is 6, 20 and 6. Shares sold short as a percentage of each company's float coincidentally total 38%.

Since our Jan. 29 story on National Oilwell Varco (NOV) and NOW, Inc. (DNOW), the former share price has declined by 3.2%, the latter increased by 33.6%. The difference, we think, is attributable to the fact that DNOW was closer to the brink than NOV. Certainly, ATW is financially weaker than RIG, therefore riskier, and--therefore--more susceptible to the joyous relief imparted by the lifting of bankruptcy fears. Each remains a speculation.

•

Not a subscriber? Click here