Drug dealer

Posterity, rubbing its eyes, will marvel at many things we now take for granted. Financial posterity may look back with particular amazement at Valeant Pharmaceuticals International (VRX on the New York and Toronto stock exchanges). The rise and--we now tip our analytical hand--fall of this razzle-dazzle deal-doer is the subject under discussion.

In Valeant, a financialized age has produced a financialized pharma company. You hear great entrepreneurs say that they didn't set out to achieve wealth or a towering share price--financial success simply followed commercial achievement. Valeant, under the leadership of CEO and Chairman J. Michael Pearson, gives pride of place to stock market capitalization in expressing its grand strategic vision. In the January "guidance" call, Pearson vowed to make Valeant "one of the top-five most valuable pharmaceutical companies as measured by market cap by the end of 2016. This equates to roughly $150 billion of market cap."

Grant's is bearish on Valeant. To declare an interest, Kynikos Associates, which employs your editor's elder daughter and whose founder and CEO, James S. Chanos, has subscribed to this publication for 30 years, is the source of the idea. Not that we blame Kynikos of any errors or misconceptions that might have crept into the following analysis. Here at Grant's, we make our own mistakes.

Anyway, we are confidently bearish, which, in view of the opacity of the corporate structure, is saying something. As you will presently see, Valeant grows by serial acquisition. Accounting for those acquisitions leaves all but the most determined analyst--in this shop, that would be Evan Lorenz--wondering which corporate end is up.

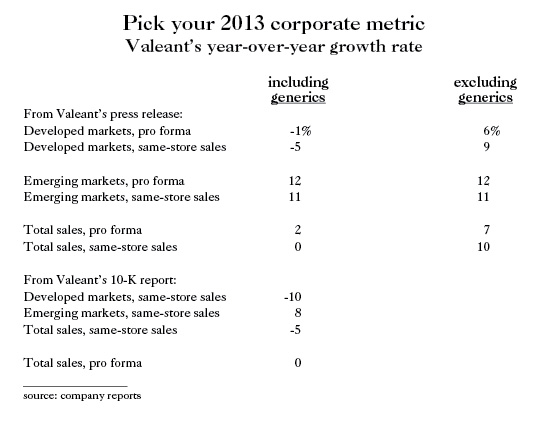

Valeant’s year-over-year growth rate

At a glance, nothing about Valeant seems too far out of the ordinary. It's an international (not, management emphasizes, "global") pharmaceutical company that focuses on dermatology, ophthalmology, branded generics and over-the-counter medicines. It sells over 1,500 products, directly or indirectly, in over 100 countries. In the fourth quarter, the United States, Canada and Australia together contributed 76% of revenue, emerging markets the balance. In 2013, Valeant generated revenue of $5.8 billion; it reported GAAP net income of minus $866 million and non-GAAP "cash" earnings of $2 billion. There are 333.1 million shares outstanding; it's an easy stock to borrow (though--as the track of the share price suggests--not an easy short to manage, or to sleep with).

The closer you look, the more you see what sets Valeant apart from its pharmaceutical peers. R&D spending is one of these eccentricities. Last year, Valeant invested just 2.7% of its sales into research and development compared to an average of 13.8% of sales for Johnson & Johnson, Pfizer Inc. and Merck & Co. Valeant does most of its compound-hunting in the stock market, not the laboratory; it acquired more than 25 companies in each of the past two years.

"Valeant is no ordinary pharma company," observed BMO Capital Markets analyst Alex Arfaei last year in his first report on the company. "The notion that a pharmaceutical company would essentially quit R&D and rely on acquisitions for growth is still discomforting, if not absurd for many reasons. Yet that is Valeant's expertise: the ability to identify inefficiencies in its target companies, pursue them aggressively while maintaining the discipline to not overpay, and successfully integrating the acquired companies in a more efficient, decentralized structure with a low tax rate. We argue this (now demonstrated) expertise is as valuable as a productive R&D engine because Valeant is applying the strategy in the right markets."

Certainly, the stock market's a believer. Since Pearson took the helm on Feb. 1, 2008, the share price has risen by 2,174%, an upsurge in which the CEO has himself amply participated. The former director and head of McKinsey & Co.'s global Pharmaceutical Practice, Pearson owns 3.4 million Valeant shares worth $486.5 million today. Depending on this year's price action, the boss stands to receive between 120,000 (if the price is $83 on certain measurement dates) and 480,000 (if the price is $224 on certain dates) performance-based, restricted stock units.

Enough said--for now--about the stock. What about the business? Managing the business gets half of management's time; M&A opportunities absorb the rest, according to the chief financial officer, Howard Bradley Shiller. So much in thrall is the Street to Valeant's alleged deal-making prowess that one analyst, at least, goes to the remarkable length of penciling in "unannounced deal flow" as a major source of future Valeant earnings power.

So many deals, so much confusion. You begin to wonder if anyone outside the front office actually understands what the company's about or what it earns (about which more in a moment). Consider, says Lorenz, "the 2012 Valeant purchase of Medicis Pharmaceutical Corp. for $2.4 billion cash (Valeant always pays cash). Pre-acquisition, Medicis had recognized revenue not when it shipped its products to its distributor, McKesson Corp., but when McKesson sold those products to doctors. Post-acquisition, Valeant began booking sales as soon as the McKesson-destined products went out the door. In response to a query from the SEC, management defended the new practice. (Valeant's pricing policy, as distinct from Medicis, allowed greater certainty as to revenue was the essential response.) One is left to wonder what changes Valeant has chosen to effect in the numerous smaller acquisitions that never produced a similar regulatory paper trail."

Valeant’s net debt and pension obligations (left scale) vs. free-cash flow per share (right scale)

Not even Valeant always knows exactly what it's getting. How could it when--for instance--Bausch & Lomb, a 2013 acquisition for which Valeant paid $8.7 billion, has not undergone an outside check on internal controls since 2007, when private-equity buyers took B&L private?

Implicit in the bull case for Valeant is that good things happen to the companies that Valeant buys. We don't see the data to support the contention. Thus, Lorenz observes, "Valeant talks about organic growth excluding drugs that lose patent protection--another variation on the old 'earnings-before-the-bad-stuff' method. Management also confusingly tabulates year-over-year organic growth in different ways. One way is as if Valeant controlled all acquisitions for both the current reporting period and the year-ago period. Another is on a kind of same-store-sales basis, which measures year-over-year performance without the impact of acquisitions. Indeed, in any given period the company may present five different growth rates: 'headline,' organic same-store sales including generics, organic same-store sales excluding generics, pro forma organic growth including generics, and pro forma organic growth excluding generics. Any questions?

"In 2013," Lorenz proceeds, "organic same-store sales growth, including generics, was a negative 5.1%, driven by a 10.4% decline in developed markets and an 8.5% gain in emerging markets. On a pro forma basis including the impact of generics, total sales declined by 0.5%. The fact that same-store sales are declining at a more rapid rate suggests that the longer a business is under the Valeant umbrella, the worse it performs."

It's not as if Valeant isn't pulling the levers to grow. It works hard to avoid tax, and it methodically raises prices on the products it acquires through M&A. The latter policy, especially, has prompted some analytical questioning: "We previously raised questions regarding adverse volume growth and the sustainability of large price increases for VRX's prescription derm brands. . . ," Bank of America/Merrill Lynch analysts noted last summer. "[W]e believe it is notable that volume trends have deteriorated for many of the large branded drugs that VRX has acquired."

Always, the conscientious shareholder will ask, "What do I own and what do I owe? And what do I earn?" As to the first point, in 2013, Valeant spent $5,323 million on acquisitions, up from $3,559 million in 2012. At year-end 2013, the balance sheet registered an $8.2 billion jump in goodwill plus intangibles to $22.6 billion. Net debt, including pension obligations, jumped to $16.9 billion from $10.1 billion. In the fourth quarter, GAAP operating income of $223 million fell short of $260 million in interest expense. Since 2010, revenues, the share price and net debt plus pension obligations have described similar fireball growth arcs, up at compound annual rates of 69.7%, 73.1% and 74.4%, respectively.

"What do I earn?" On a GAAP basis in 2013, Valeant showed a loss of $2.70 a share vs. a GAAP loss of $0.38 a share in 2012. Management asks that you avert your eyes from those unsightly data to focus instead on "cash EPS," a forgiving metric of its own creation. Cash EPS subtracts from income acquisition-related expenses, goodwill and intangible amortization costs; also, write-downs, legal settlements stemming from acquisitions and other "one-time" costs. On this bespoke basis, Valeant "earned" $6.21 in 2013 vs. $4.51 in 2012.

Valeant can say it "earned" $100 a share. If you buy growth in the stock market (and in the debt market), are the aforementioned attendant costs not real enough? In Valeant's case, especially, are they not recurring enough?

So, then, what does Valeant really earn? "Cutting through GAAP and non-GAAP earnings," Lorenz proposes, "let's settle on free cash flow--that is, cash flow from operations less capital expenditures. In 2013, free cash flow amounted to $927 million, or $2.89 per common share, up from $549 million, or $1.80 a share, in 2012. The 2013 reading would give Valeant a less-than-lordly free-cash flow yield of 2%. Unlike R&D expenses, which are debits in the free-cash-flow calculation, funds spent on acquisitions don't impact free-cash flow. As Valeant conducts its R&D via M&A, free-cash flow, if anything, flatters Valeant's ability to generate cash."

On the fourth-quarter earnings call last week, an analyst asked the Valeant CEO about a possible merger of equals between his company and a player to be named. "First of all," Pearson replied, "in terms of the number of opportunities out there, we would say, it's not five, 10 or 15, it's probably closer to 50 in terms of opportunities. . . . [W]e're in multiple discussions and we always have been and will continue to be. And when an opportunity is--when the opportunity comes--we'll move on it."

To that prospective merger partner, we would ask this simple question: Are you quite sure you know what you're getting yourself into?

•

Not a subscriber? Click here